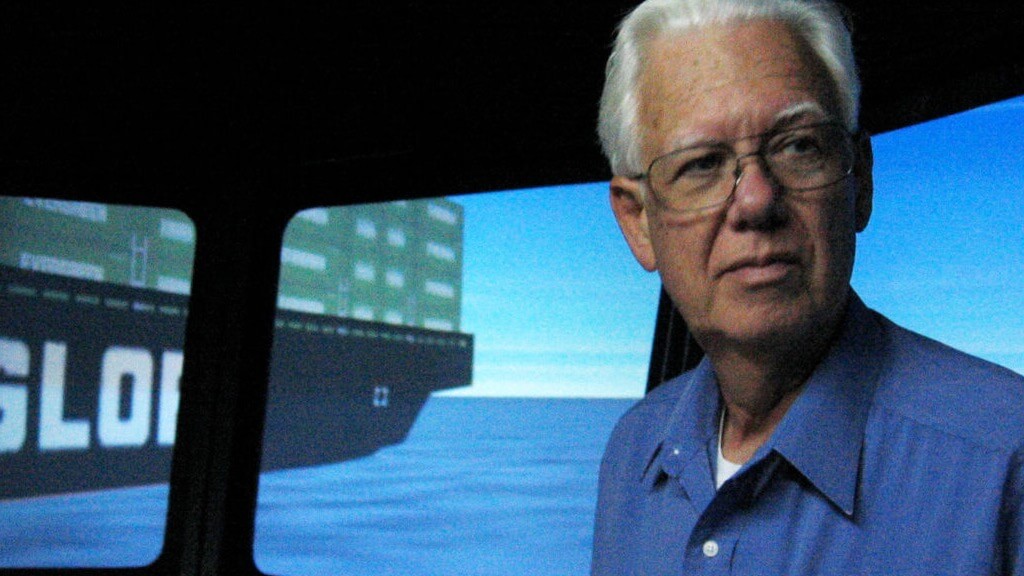

Richard Lindheim was ICT’s first Executive Director (1999 – 2006). Previously, he was an entertainment executive, responsible for shows such as Frasier, Star Trek Voyager, Deep Space 9 and Miami Vice. As EVP of the Paramount Television Group, he established Paramount Digital Entertainment, the studio’s Internet technology group. Richard Lindheim died in 2021 at the age of 81. This essay is adapted from his memoir THAT’S A 40 Share! with the kind permission of his family.

“What’s the value of having Hollywood creative people engaged with real-world problems?”

That was the question raised by the Defense Department, which realized that its suppositions and response scenarios were rapidly outdated by current events. My involvement with trying to answer that question suddenly changed my life and career.

My job at Paramount Television at the time was to look for new opportunities to expand television creation and production to other endeavors, such as a Star Trek location-based entertainment center in Las Vegas. I was also exploring international co-production activities and developing special relationships with advertisers that could be integrated into shows. This latter was a continuation of work I had done as an executive at Universal Studios.

One day Alex Singer, the veteran TV director, came to my office and told me that the Defense Department was coming to Los Angeles to explore a possible relationship with the entertainment industry.

I asked him what they had in mind: “Propaganda films?”

Alex said he had no idea, but that there was going to be this workshop on a Saturday at the Beckman Center in Irvine. Would I attend?

I was intrigued. What could they possibly want from Hollywood? I told Alex that I would. He was delighted. I thought I could do the usual Hollywood thing: Show up. Sit unobtrusively. Learn what was going on. Smile, shake a few hands and split. How naive I was.

When the workshop began, it took me about five minutes to understand the basic premise: The government spends billions of dollars to develop computer-based games that were used for training soldiers for specific tasks such as flying an aircraft or driving a tank, and these specially designed expensive games were not very good. Young soldiers entering the military complained about how poorly designed they were.

Dr. Anita Jones, The Director of Defense Research and Engineering (DDR&E), the person at the forefront of new technology development for the entire Defense Department, wanted to explore the viability of using commercially created games and modifying them for military training. In other words, could you take Microsoft Flight Simulator to train men and women how to fly an actual aircraft? Could you use Tank Commander to teach a soldier to drive a tank?

None of this interested me very much. Paramount did not have a computer game operation; we licensed outside companies to develop games from various Paramount properties such as Star Trek. I also was aware of the limitations at the time of the medium.

During a break, Anita turned to me. “What do you think?”

I didn’t want to be critical or unappreciative of what she was looking to accomplish. I mentally composed my answer before speaking. “I get it. But all of this is confined to teaching manual skills to soldiers in the field. Is there any interest in teaching officers how to make better decisions to become better leaders?”

Her response was immediate: “Yes. That would be wonderful.”

By late afternoon, I made an excuse to leave and headed home on the 405 Freeway. As I drove, it occurred to me that there might be a way to extend Hollywood storytelling expertise to leadership training. I wondered if it would be possible to construct an interactive story where the officer being trained is faced with a number of decisions, and where their decisions have direct impact upon the story being told.

To keep the story from going in some crazy, undesired direction, there would be “bumpers” placed on the storyline. If the player got too far away from the desired play area there would be a thunderstorm, or a forest fire, or a major auto accident that would prevent continued movement in that direction. The player would be forced to turn around and find an alternative. And the only suitable alter native would be within the “play area” of the game. I thought we might call it the StoryDrive Engine.

On Monday I called Alex into my office. I told him the idea of the StoryDrive Engine. He thought it was interesting. I told him that, since he had gotten me into this mess, I wanted him to go back to D.C., meet with Dr. Jones, and present the idea. He agreed to do it.

When he returned from a visit at the Pentagon, he was excited. Dr. Anita Jones wanted to do StoryDrive Engine. I was excited as well. This would definitely be a new kind of project. My boss at Paramount Television, Kerry McCluggage, was slightly dubious but supportive.

The project was assigned to the Defense Modeling & Simulation Office (DMSO). Dr. Judith Dahmann would educate us about military training, and to find a pilot project that would demonstrate the value of the entertainment industry connection. She brought in several highly proficient civilian military people working with training to assist and evaluate.

On our side, in addition to Alex Singer, I enlisted the help of David Wertheimer, who ran Paramount’s digital entertainment division. I contacted my friend, Dr. Elizabeth Daley, who was dean of the USC Cinema School (now the USC School of Cinematic Arts). Dr. Judith Dahmann at DMSO suggested we contact ISI (Information Sciences Institute) at USC to bring their expertise in information processing and computers to the task. Dr. Bill Swartout and Dr. Paul Rosenbloom joined the team. An initial meeting and discussion was set at Paramount. In addition to the DMSO people, Judith had enlisted the help of several high-ranking, brilliant, retired generals and admirals.

After touring a number of military training installations around the country we ended up at Ft. McNair in Washington D.C., which houses the National Defense University. Part of the NDU is the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, renamed in 2012 as the Dwight D.Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy. ICAF was established for young officers who demonstrated strong capability to succeed; they represent the best and the brightest, the future military leaders of the country. The final exam for the ICAF course took place over a week. The officers were theoretically stationed in the “tank” at the Pentagon, where they had to deal with a series of crises. Their final grade depended upon how well they analyzed and handled these crises. It was a traditional paper and pencil test. Print materials only.

It was quickly apparent that this was the perfect place to demonstrate the StoryDrive Engine and the values that entertainment people could bring to leadership training. We recognized that we could make this training exercise realistic, interactive and immersive. In the end, we got the contract to build and operate a pilot program for ICAF.

Then, six months later, Mike Andrews, Chief Scientist for the Army, called and asked to come and meet with us at Paramount. The Army had decided it wanted to start a new institute to collaborate with the entertainment industry to create visual, interactive training. Since the military had ongoing relationships for research with various universities, they wanted to establish this institute within academia. They felt a university would be a good, neutral ground for military and entertainment people to work together.

In 1999, the Institute For Creative Technologies (ICT) at USC was announced. I was asked to become its first Director. And that began a whole new career for me, working with both the government and a major university. I found myself engaged in a fascinating learning curve over the next few years.

//